The Brief: The nonlinear journey of a nuclear engineer turned Nike designer

A guest post from Kevin Bethune, Design Better Expert in Residence

In this issue of The Brief:

Zig then Zag: Life is a Nonlinear Journey

Things to watch, read, and explore

Many of the most interesting people we speak with on Design Better have taken winding paths into their creative careers. Kevin Bethune is no exception: he went from nuclear engineering, to business school, to shaping innovative products at Nike.

In this issue of The Brief, we’re sharing a chapter excerpt from Kevin’s book Nonlinear: Navigating Design with Curiosity and Conviction. Kevin—now one of our Design Better Experts in Residence—reflects on his zig-zagging journey from engineering to design and the mindset that guided each step.

ZIG THEN ZAG: Life Is a Nonlinear Journey

by Kevin Bethune

Excerpted from Nonlinear: Navigating Design with Curiosity and Conviction by Kevin G. Bethune. Reprinted with permission from The MIT Press. Copyright 2025.

I am a product of a very windy road. I am a designer, entrepreneur, and author based in Redondo Beach, California. I am a husband, a father, and a Black man who’s navigated a very unique journey of multidisciplinary leaps. I am a descendent of America’s original sin of chattel slavery, continually imagining the strength and resilience that embodied my ancestors’ experience. I am married to an Ethiopian-born American who is more able to trace her history as far back as three thousand years from the days of King Menelik and Queen Sheba. Our teenage son represents an amalgamation of both threads of histories and cultures. He lives in a world still plagued by the threads of systemic inequity that attempt to convince him that he’s “less than” or an “other” based purely on the color of his skin. We do our best to expose him to as many things as possible so that he begins to imagine himself doing great things in the future. His dreams matter. We believe in his potential. I try not to worry as he navigates a world vulnerable to police brutality and schools unsafe from guns. I have to place my faith in God for his safety and the safety of my family. Part of recognizing who I am, and who the folks I’m representing are, is that I will consciously rebel against the challenges we face with hope, faith, optimism, curiosity, and creativity. I am.

At the same time, I should embrace another human being with equal gravity. They are. You are. There is the full breadth and depth of a person’s humanity that we should acknowledge and respect. We need to engage others with complete humility, empathy, and compassion. We are not the same, and that’s a beautiful thing. Our stories are like fingerprints: very different. Yours is no more worthy than mine, and vice versa. However, our reverence for each other should hold enough weight to spark healthy curiosity and empathy for one another. In doing so, we’ll unearth opportunities to see the common threads that lie between us, and we’ll share in a common purpose. We can do that while celebrating what makes us different.

Our stories are like fingerprints: very different. Yours is no more worthy than mine, and vice versa.

We should celebrate what we can learn about each other. At the same time, we should also recognize that we navigate much of the same world, the same spaces, and the same constructs. Aspects of my story may not directly translate to someone else, but we might identify with the same circumstances. You might be a parent, the same as me. Despite living in different cities, we may be wrestling with remote work through Zoom calls and Slack threads. We can be different and similar, at the same time. When sharing from my lived experiences, I am careful to say that I can only speak for me. Just because I experience something, I shouldn’t assume the same reality on you. I don’t want anyone to feel like they have to do exactly what I’ve done. My only hope is that you might use my story as a mirror to see yourself a little differently and find the courage to bring your full humanity to everything you do.

As we think about how we journey forward in life, the spaces and structures that we navigate are the way they are by design. They were informed by someone. When given an opportunity, we have to unravel who was actually at the table in informing these constructs and recognize the threads of systemic inequity that have persisted within them. My first book, Reimagining Design: Unlocking Strategic Innovation, shined a light on the importance of design at parity with other disciplines in informing the evolution of our spaces, enterprises, and institutions with the hope that we can inform better futures. I wrote it for anyone (regardless of discipline) who’s creatively curious and likely to be proximate to design within a multidisciplinary team. I wrote it for those who are wondering how to position themselves in a world undergoing multidisciplinary convergence to meet the complex challenges of our time, and to help them figure out how to make lasting, positive change. For design in particular, I find that designers are especially passionate about the human condition. Their arrival at the problem-solving table is surely welcome based on what the world desperately needs right now—more empathy and compassion. At the same time, their arrival runs in the face of predominant forces that have shaped industries as we know them. From business titans who set the tone of Wall Street to Silicon Valley technologists who pioneered the digitization of our world, design has an opportunity to set a new precedent, a new tone. These precedents are important as we think about bringing the right people around the table.

As we look forward, we can’t forget the underlying thread of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) to ensure the mix of folks around the table actually mirrors the world in terms of representation. Far too many self-proclaimed “world-class” brands and organizations claim to “design for” or “build for” their customers. However, when you peer inside their hallways, their team composition fails to reflect the beautiful diversity of our society. It’s even worse when it comes to their leadership pipelines and board rooms. They will claim rightful position based on a shaky premise of meritocracy and how they ascended career ladders of hardened pedigree. Considering the threads of systemic inequity and the paradigms of power and privilege, is it really that simple? Does it explain why so many are left out? Upon examining their understanding of customers and stakeholders, we usually find significant amounts of bias and blind spots between their offerings and what people actually need. These issues could be avoided if they respected their audience with humility and brought them into the process (i.e., if they opted to design with or build with). I will boldly say that we need to go even further. Beyond designing with, we need to ensure our teams actually include representative members of our diverse society. Representative teammates could broker authentic inroads into those communities that we have yet to authentically engage. Within design, I find the low percentage of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, people of color) professionals especially disappointing. Our future teams should mirror the beautiful tapestry that is the world.

Even if a team is multidisciplinary and more diverse by representation, I’ve learned that who’s at the table isn’t enough. How that team actually navigates through the work is extremely important too. We have to think about what we expect a multidisciplinary, diverse team to do when facing any opportunity to create something new. Each person brings their own perspective, behaviors, language, and skillsets. Even starting with the basic question of “Who should lead?” opens the door for all kinds of baggage to be revealed. If we remember the dominant precedents that inform the status quo for most organizations, we’ll quickly realize the existence of biases as it relates to leadership tact, collaboration behavior, and the exchange of what people ultimately value. When we think about the disciplines around the table, certain individuals might quickly snap into a particular way of doing things and expect others to follow suit. Depending on the level of political capital around that table, some disciplines may immediately get their way while others are quickly subordinated, sometimes without knowing it. This can resemble an expected march of expectations: I do this, then you do that. Once you’re done, I expect you to pass that output along to the next person and she does this, and so on. Over time, these transactional behaviors start to harden and become engrained in the company’s way of doing things. It becomes the precedent.

This dilemma grows the bigger a company becomes. Any new approach is usually met with skepticism. Any technique that slows down the cadence of problem-solving might be viewed as heresy. More than likely, departments would rather lean into their proven and tested playbooks under most circumstances. Playbooks inform workplans, what language to use (especially jargon and acronyms), and recommended work cadence, and the nature of the work becomes very predictable. There may not be any room for experimentation or thinking outside the box. With more scale, sometimes that’s reasonably expected as teams need to stabilize the boat in choppy waters. New people coming into a company should learn to master the fundamentals of the core business before attempting to change it.

Design is probably the least understood and most underrated entity when the team comes together.

I can’t fault the desire for predictability in that instance. However, when it comes to innovation, using conventional approaches may actually backfire. As multidisciplinary teams come together, what happens when the playbooks need to blend or intertwine to balance out different working styles? What does it mean to figure out something new versus working on what was previously routine? How will we handle the gaps of understanding between disciplines as they begin to work toward “what’s next”? Design is probably the least understood and most underrated entity when the team comes together. Conversely, the designer, product manager, or technologist might struggle to understand what motivates the businessperson. When navigating the pursuit of innovation, we need to overcome these gaps of understanding.

In parallel, as we imagine increasing the representative diversity in our teams, each person brings uniquely different lived experiences. Are we ready to have our playbooks and precedents interrogated by different folks that show up with uniquely different points of view? Are we making them feel welcome to do so? What if they recommend different ways to engage target demographics because they actually come from those demographics and can better appreciate the cultural nuances at play? I’ve had experience building teams in situations where the present playbooks of the day were not relevant against the new opportunities we faced. We literally had to scour the earth for diverse people who could challenge us with their different perspectives and make us and our methods stronger in relationship to imminent opportunities. After a few years of doing that, I looked back and realized that we had assembled the most diverse team I had ever served and led. Our approach to the work ended up becoming more nimble, fluid, and adaptive to different audiences and needs. With a vibrant mix of races, genders, cultures, backgrounds, and philosophies represented, the teams actually found incredible inspiration from each other. Their aperture was wide open, and they were more astute when nuances emerged in the marketplace. As a result, our methods didn’t stagnate to the point of becoming formulaic. Upon reflection, design, with its inherent strength of empathy, served as an important catalyst and leading voice in accelerating these dynamics across our diverse team.

Nonlinear: Navigating Design with Curiosity and Conviction illuminates design’s nuances and complexities as a source of nonlinear advantage within your multidisciplinary innovation endeavors. Yes, there’s actually an advantage to taking a nonlinear, less than formulaic approach! Every step we take in the journey is what I would characterize as a vector. Let’s unpack the Merriam-Webster Dictionary definition of the word vector: “A quantity that has magnitude and direction and that is commonly represented by a directed line segment whose length represents the magnitude and whose orientation in space represents the direction.” We can associate the word magnitude with the effort or the amount of work you’ll put in to fulfill a step in the journey.

There’s something to be said for cultivating the momentum necessary to learn as fast as you can before investing everything you have into an idea.

Then there’s the actual direction of that effort. Is it a push to learn more about a target audience? Is it moving forward to commercialize a new solution? Is it pivoting and changing course based on new learnings? Or is it looping back to retread old ground because you discovered a flawed or radically new assumption? I’ll use the word vector a lot to describe different steps we might take, and I’ve learned it’s not about a right or wrong vector. It’s about momentum. There’s something to be said for cultivating the momentum necessary to learn as fast as you can before investing everything you have into an idea. You have to make do with the best information you have, one step at a time. Movement will feel like art and science. Movement will involve the left brain and right brain. Movement is further empowered by DEI to ensure that we have brave teams that celebrate people’s differences and thus to ensure our aperture is wide open in terms of how we perceive the evolving world.

One of my favorite speeches is from my creative hero Denzel Washington, the famous Hollywood actor, movie director, and Broadway performer. In his commencement address to the 2011 graduating class at the University of Pennsylvania, he said, “To get something you never had, you have to do something you never did,” reiterating a growth affirmation received from his wife. Repeating and rehashing what has been done before might be a surefire way to inhibit innovation. Even with the success of design thinking permeating enterprises over the last few decades, we’re still at the beginning stages of the business world fully comprehending design and its capabilities. Design is so much more than whiteboarding, Post-it notes, and rapid design sprints. You can’t solve all the world’s problems in a hackathon or a one-week sprint. The world is far too complicated, and applying formulaic rinse-and-repeat approaches might yield mediocre outcomes or, even worse, induce harm if we don’t thoughtfully consider and respect the complexity we’re facing. Also, allow me to be a bit frank: Design will not save the world by itself. It can’t do it in a vacuum. When partnering at parity with other disciplines at the problem-solving table, then we’ll have something. We’ll have a shot to use our collective creativity, diversity, and nonlinear approaches to shake things up and inspire meaningful change that we can realize together.

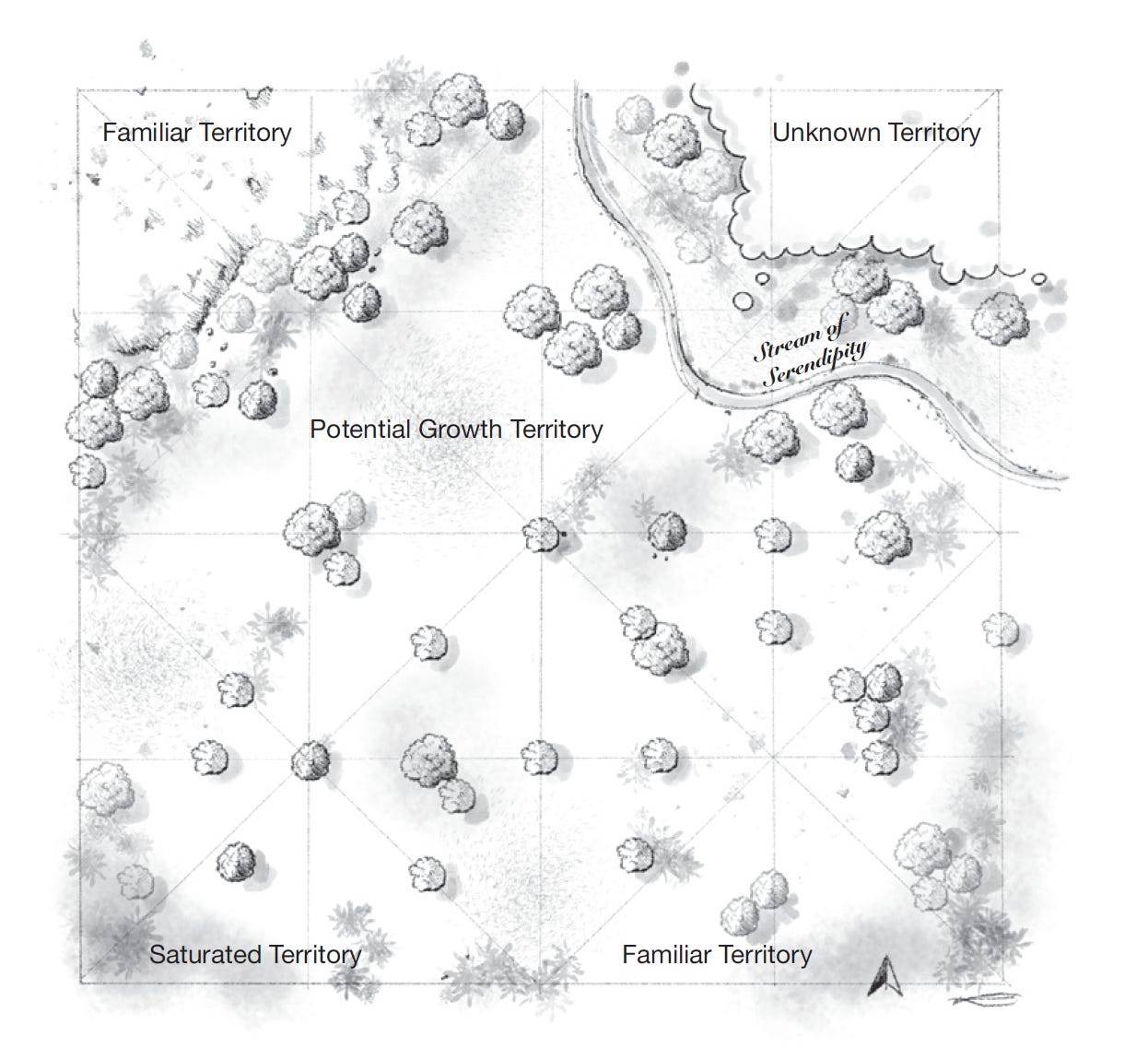

I write these assertions from direct experience navigating situations in which the path wasn’t always clear, or I found myself in places where my brewing convictions didn’t match what the job or what others expected of me. I was literally in a forest of ambiguity trying to find a new way. I like to use the metaphor of a forest (see figure 1.1) to explain how I think about navigating ambiguity in pursuit of innovation. My proclivity for ambiguity actually started from the very beginning of my career and continues up until this day. Before I go further, I want to be clear that I haven’t navigated perfectly. I made plenty of mistakes and hit my head against many brick walls. My hope is that you glean insight from my experiences, both good and bad, to appreciate the nuances of navigating innovation work and understand how your career and lived experiences play an important part. No matter the discipline you represent (e.g., businessperson, designer, product manager, or technologist), I will confidently assume that you are a creatively curious person that knows they are navigating a world that’s becoming more complex, connected, and accelerated. You need to maneuver in such a way that you can seize that momentum for learning, but perhaps in different ways that you haven’t been accustomed to. Because I have had to navigate some early and very unique situations that are now interpreted as multidisciplinary innovation, please allow me to be your guide. Why me? To answer, I’ll tell you more about my story of multidisciplinary leaps and lived experiences.

During my youth, when I had glimmers of imagining what I would do for a living, I wrestled with a lot of curiosities. Before work became work, I had hobbies. Mine was drawing. That was my way of seeing the world, interpreting what I saw, and expressing what I conjured up within my imagination. My parents did what they could to feed that creative itch by exposing us kids to a wide variety of things. Being raised predominantly near Detroit, the heart of the American automotive industry, the working culture of the region favored pragmatic disciplines like engineering and business over the arts. Notions of design or innovation were far outside my purview, for right, wrong, or indifferent. I chose mechanical engineering as a first step because of my affinity for math and science, on top of my knack for drawing. I attended the University of Notre Dame and braved the cold weather months navigating its tough engineering curriculum. It was difficult, but the program made me resilient. I learned how to wrestle with problems longer. My engineering education taught me how to make sense of a physical world, to understand how things work. Upon graduation, I channeled my learnings toward one industry that offered a significant runway of opportunity compared to most others. The nuclear power industry hadn’t hired young talent for the ten to fifteen years prior to me coming out of school. They were concerned about the drain of knowledge with impending retirements and made an aggressive play for new talent. It was my opportunity to slip through a wide-open door (getting hired by Westinghouse Electric Company) that would lead me to incredible learning opportunities.

As a mechanical engineer, visiting a nuclear power plant in the throes of a maintenance outage was absolutely awe inspiring. When you set foot inside a nuclear containment building, your first instinct is to look up. The sheer size of everything takes your breath away. Steam generators reach up to the upper echelons of the dome-shaped containment building.

As a young engineer, I had to see projects through the steps of discovery, design, engineering, and analysis of hardware solutions; tooling and fabrication; and bringing a complete service intervention to the field to fix or upgrade each plant.

Looking below your feet (usually through a grated metal floor), you’ll peer through several stories of infrastructure, where coolant pumps, piping, instrumentation, and the like all reside deep below. Looking forward, you’re greeted with the sight of a very large swimming pool filled with shimmering coolant water of an aqua-blue hue. This water is actually used in the closed operating system when the plant is buttoned up and running at power. As a young engineer, I had to see projects through the steps of discovery, design, engineering, and analysis of hardware solutions; tooling and fabrication; and bringing a complete service intervention to the field to fix or upgrade each plant. I learned a ton through the first few projects, mastered the next few, and eventually had the privilege of leading several end-to-end efforts. Some projects were routine, some projects required new innovative approaches, and some were emergent projects responding to a critical emergency. My technical skills were tested, and my leadership muscles were challenged at every step. In the process, I started to grow curious about the larger strategies surrounding every engineering project and started asking questions in an attempt to comprehend the larger business dynamics at play.

At the same time, I noticed that if you’re pretty good at your engineering projects, a company tends to ask you to do that work over and over again, especially as your work directly drives the company’s revenues. That’s great for folks that love doing that specific work, and there is surely incredible honor in doing it. For me, I felt like a different choice was brewing that would affect the trajectory of my career. I felt I could either double down on my engineering pedigree and become a deeper expert on my projects, or I could widen my aperture to understand those business dynamics that orbited my engineering work. This lingering curiosity drew me to make friends with the marketing department. I found opportunities to engage in stretch assignments in which I could use my engineering experience to help the marketing team inform new proposals. In doing so, I was able to scratch that itch to learn more about commercial matters as we negotiated work with our nuclear-owning utility customers. Despite having my contributions valued, I felt that my business acumen was sorely lacking to be able to connect the dots effectively and command any strategic influence. If I didn’t address that gap, my imminent career choice would be made for me, and I knew at the time that I wanted a bit more agency to make that decision for myself.

Fast forward, my curiosities from early commercial exposure led me to pursue an MBA to shore up the language for business I lacked as a technology professional. I attended the Tepper School of Business at Carnegie Mellon University. Tepper was particularly empathetic toward engineers looking to add that layer of business acumen, so it was a great fit for me. I really enjoyed my classes, the faculty, and the Tepper community at large. Their culture embraced this idea of connecting the dots across disparate market forces, and they were willing to change or experiment with their curriculum to match the emerging needs of the marketplace. For example, my MBA journey started in the aftermath of Enron, so ethics became an important thread through several of my classes. Personally, I had to contend with a plethora of new voices and perspectives about what this business degree could mean for me and my future: “To build wealth, you should go into investment banking.” “For power and influence, head into management consulting.” I felt my own voice withering a bit as I was learning new skills while also trying to envision the type of future that would be right for me. But I did eventually remember that voice of my inner child who used to draw all the time for enjoyment. I let that creative itch begin to guide which companies and industries I pursued. Technology and business models wouldn’t be enough; I wanted to join an organization that had creative faculties as well. I wasn’t sure what that would mean for me, but I felt my heartstrings being tugged in that direction and looked for companies that embodied a mix of multidisciplinary capabilities.

Companies like Apple and Nike rose to the top of my wish list because they embodied that mix of creativity, business, and technology. I felt I could learn a ton in their environments. I never got a chance to talk with Apple but happened across Nike at an MBA career fair. Thankfully, Nike afforded me a path to join upon graduation. I started as a business planner (a typical post-MBA job) at Nike World Headquarters in Beaverton, Oregon. Our team’s mission was to roll up financial and operational performance across different Nike business segments and provide objective analyses to Nike senior executives to help them in their decision-making and quarterly communications with Wall Street. We literally combed through the numbers, unearthed the stories behind the numbers, and wrote the talking scripts that executives would leverage in their conversations with Wall Street analysts during the quarterly earnings release calls: “Why were inventories up? Why was marketing spending down this quarter? Why did gross margins increase?” I was mindful to the needs of this first position, and it surely helped me solidify my business acumen in wrestling with the realities of a publicly traded company of the stature of Nike, Inc. I really appreciated the managers of that group taking a bet on me, someone who didn’t come from a conventional business background from the very start of my career.

However, I was truly a product person at heart. I didn’t want my business experiences to take me completely away from product, nor the art of invention. To scratch my product itch, I started networking across Nike to look for those kindred spirits doing that type of work. One coffee chat led to another, and so on, until I found opportunities to engage in stretch assignments (i.e., side hustles) to learn from those teams while also showcasing my potential through the act of doing. Eventually, I was able to navigate over to Nike’s global footwear product engine, where I encountered professional design being practiced for the first time in my career. Design was also nested in close collaboration with engineering, product management, and business. I knew it was the right environment for me to ask a lot of questions and observe their methods. While making friends among the design community, I shared drawings that reflected my hobby and raw creative skill. Conversations with superstar creatives such as Tinker Hatfield, Angela Snow, Michael DiTullo, Albert Shum, Suzette Henry, Jason Mayden, Jeff Henderson, Natalie Candrian Bell, Eric Avar, and Bruce Kilgore motivated me to keep moving forward in scratching my curiosities. One conversation opened a doorway that would change my life and trajectory. I had a chat with the Jordan footwear design director at the time, a man by the name of D’Wayne Edwards (who is now the president of Pensole Lewis College of Business and Design). He saw my raw creative skill and gave me my first shot to design footwear.

I would meet Edwards in the early mornings to commiserate on a brief that didn’t have a designer assigned. After our morning sessions, we would then peel away to do our day jobs, and I would later work on his stuff until the wee hours at night. Rinse and repeat every day for a year, and we birthed two footwear models under my design credits and his mentorship. That opportunity led to other stretch assignments in different parts of Nike as I continued to cut my teeth on early footwear design work. Little did I know these stretch assignments were bringing me to a major fork in the road. On one hand, I could claw and scratch through more side hustles for another ten to fifteen years before I would be fully pedigreed as a footwear designer in Nike’s eyes. On the other hand, I could invest deeply into my creative foundation through a different path. By paying attention to how the world was moving outside Nike to appreciate multidisciplinary convergence, I was open to alternative ways to learn and garner more experience. After some soul searching, I chose the alternative path and decided to quit my Nike job to go back to graduate school (I thought I was done with school!) to accelerate my learning. This move would also cement my career positioning to focus on innovation moving forward. To step away from the workforce for another two years meant an incredible sacrifice, but not just for me. My wife was also at Nike, and we just had our first and only son. The evidence trails from my stretch assignments helped her see and believe in my vision. For our son, we eventually wanted this decision to serve as an example of what it means to go after your dreams.

Intrigued by what you’ve read so far? Buy the book at MIT Press.

Things to read, watch, and explore

Explore: LOVE HULTÉN: Nostalgia and craftsmanship intersect in these custom electronic mysteries from Sweden.

Explore: Nostalgic for the simple days of black & white Macs? 🎨 Try Macpaint in the browser.

Read: Mid-century designers George Nelson and Robert Probst tried to re-imagine the workspace, but the resulting cubicles became the opposite of their design intent.

Watch: David Kelley, founder of IDEO and the d.school, recently celebrated 50 years at Stanford. In this video he talks about working with Steve Jobs, and his life-long quest to inspire creative confidence across all ages and professions.

Watch: In this Opinion Video from The New York Times, Jack Conte—the chief executive of Patreon and member of the bands Pomplamoose and Scary Pockets—explains how he’s trying to design an algorithm that won’t rot your brain.

Become a premium Design Better member to unlock our monthly AMAs, The Design Better Toolkit, and our full library of books.