What history teaches us about the struggle between humans and machines

An excerpt from the book Designing for Emotion

I’ve been thinking a lot about the tension between humans and machines lately. This year’s headlines have been filled with ominous predictions of AI-driven dystopia, countered by equally confident promises of progress and prosperity. The debate feels familiar.

We’ve been here before. During the Industrial Revolution, people wrestled with the same fear—that machines would eclipse humanity. Today, we’re seeing early signs of a similar pushback: frustration with “AI slop,” and a renewed appreciation for things made with craft, intention, and a human touch.

Chapter 1 of Designing for Emotion explores this very theme and makes the case for embracing what makes us distinctly human. We’re sharing the full chapter here in hopes that it helps you look at your work with fresh eyes.

The complete book—and our full library—is available to our Premium subscribers.

Revolution: Something Lost and Something Found

Powered by a chain reaction of ideas and innovations, a revolution of industry swept the Western Hemisphere in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In a relatively short time, we discovered ways to transform mined materials into manufacturing devices, transportation systems, and agricultural tools that fueled the twentieth century’s explosive modernization. Inventions like the cotton gin, machine tools, the steam engine, the telegraph, and the telephone promised a future filled with technological innovation that produced significant industrial advantages.

Though the Industrial Revolution sprang from a utopian vision of innovation, millions were exploited or enslaved in the process. Industrialization put the machine of innovation first and human needs second.

As the machine found its place in our world, the human hand’s presence in the production of everyday objects slowly faded. Factories that could produce goods faster and at a lower cost replaced skilled craftspeople like blacksmiths, cobblers, tinsmiths, weavers, and many others.

But some challenged the march toward industrialization. As mass production expanded in the mid-nineteenth century, artists, architects, and designers founded the Arts and Crafts movement to preserve the artisan’s role in domestic goods production, and with it the human touch. The founders of the movement revered the things they designed, built, and used every day. They recognized that an artisan leaves a bit of themselves in their work—a true gift that can be enjoyed for many years.

In the present day, we can see parallels. A quest for higher crop yields and lower production costs has transformed farms into headless corporations pitting profits against human welfare. But local farmers are finding new markets as consumers search for food produced by people for people. While big-box stores proliferate disposable mass-market goods, platforms like Etsy, Kickstarter, Shopify, and Squarespace empower artists, craftspeople, and DIY inventors who sell goods they’ve designed and created.

Enmeshed in the goods we buy from independent artisans is the human touch—a careful consideration of details that shape the user experience. It resonates, offering evidence of the maker and connecting us on a human scale. There is great power here and a lesson for us as we design digital experiences.

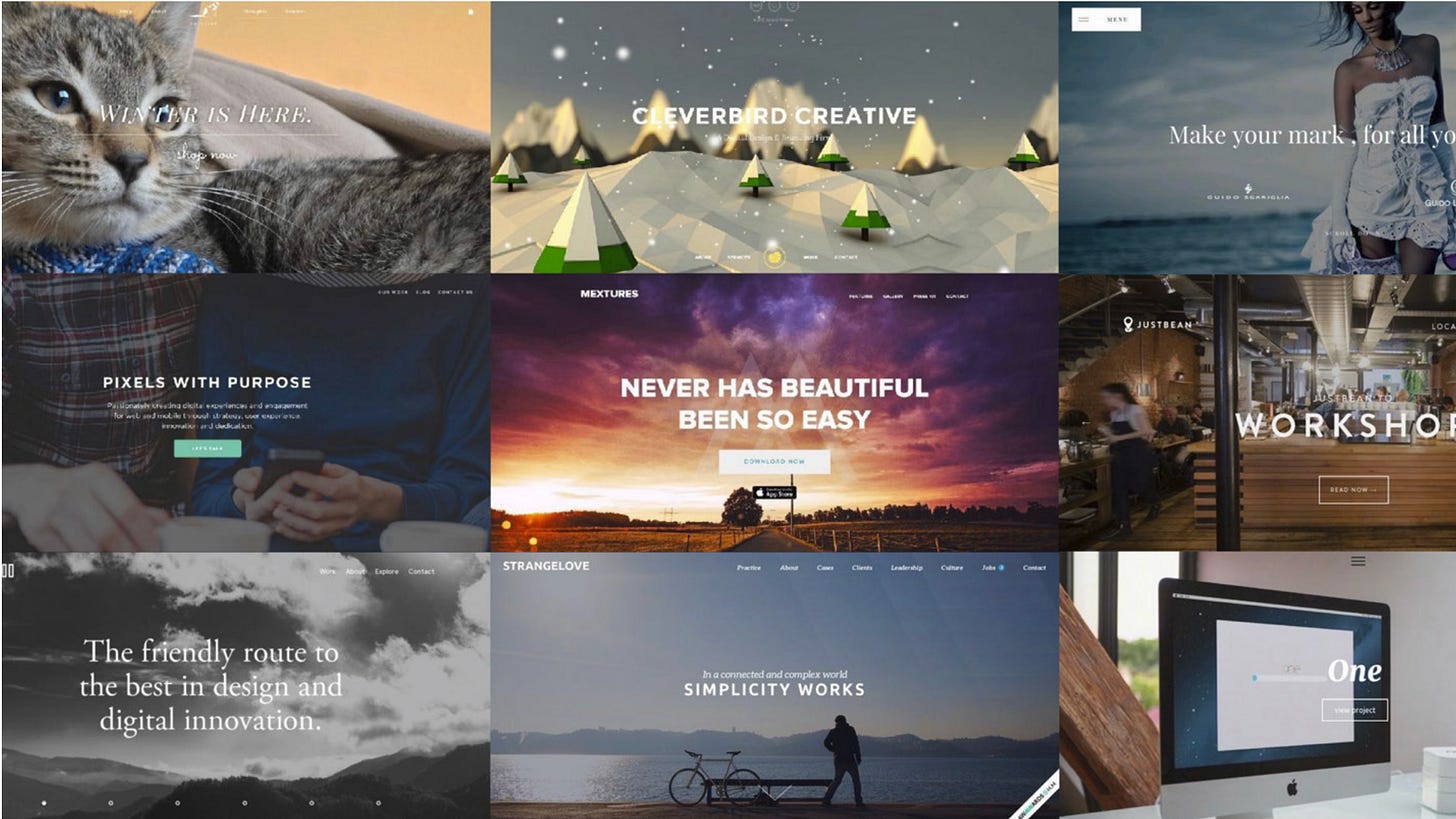

There are plenty of opportunities to build fast and cheap with no reverence for craft or the relationship we have with our audience. Frameworks like Bootstrap make it easy to build from boilerplate, but the results, like mass-produced products, are indistinguishable from others.

Fig 1.1. As Sarah Parmenter pointed out in “Practical Branding,” many websites use boilerplate elements, trading creativity for convenience. The result is that so many websites look the same.

While the human touch doesn’t exist physically in digital design, the ethos of it does. Designing for emotion—creating things that transcend function to engage us on an emotional level—is attainable in all mediums, physical or virtual.

The dawn of the Industrial Age began with optimism but gave way to recognition that what we’d created had come at a price. I hear echoes of the past as we navigate the web we’re building today. What we’ve built is equally revolutionary, but its impact is coming into focus.

The Way We Were

Like many designers, I had an optimistic view of the web back in 2011 when the first edition of this book was published. Modern mobile devices, faster wireless connections, new social platforms, and a pervasive entrepreneurial spirit fueled my optimism. It felt like a golden age when design and the web could transform lives for the better.

I thought social platforms would give voice to the marginalized, that evolving digital products would empower creativity, and that unfettered access to information would lead to a more democratic and equitable world.

Some of that came true. But, like our industrialist ancestors, I was naïve to the worst-case scenarios that could arise, and I wasn’t alone.

Today, I’m more cynical. Grim news of how the web is used nefariously for political or financial gain seems unending. Social platforms, in my judgment, are doing almost as much harm as good, and many digital products are not inclusive because there’s still too little diversity in the groups designing and building them.

It’s time to point ourselves in a new direction. Intentions may be good, but outcomes don’t always match our vision. We need to evolve our approach.

In this second edition, we’ll build on the key emotional design principles from 2011 and introduce new ones that help us meet today’s challenges. We’ll get a fresh perspective on designing human experiences filled with emotions—good, bad, and everything in between. And we’ll look at how design can create belonging and build trust, particularly when we prioritize diversity and inclusion.

Finally, I want you to take away more than principles—I want you to have conversation starters about the business value of emotional design so you can speak convincingly with engineers, PMs, executives, and stakeholders.

So where do we start? With understanding the needs of the people we’re designing for.

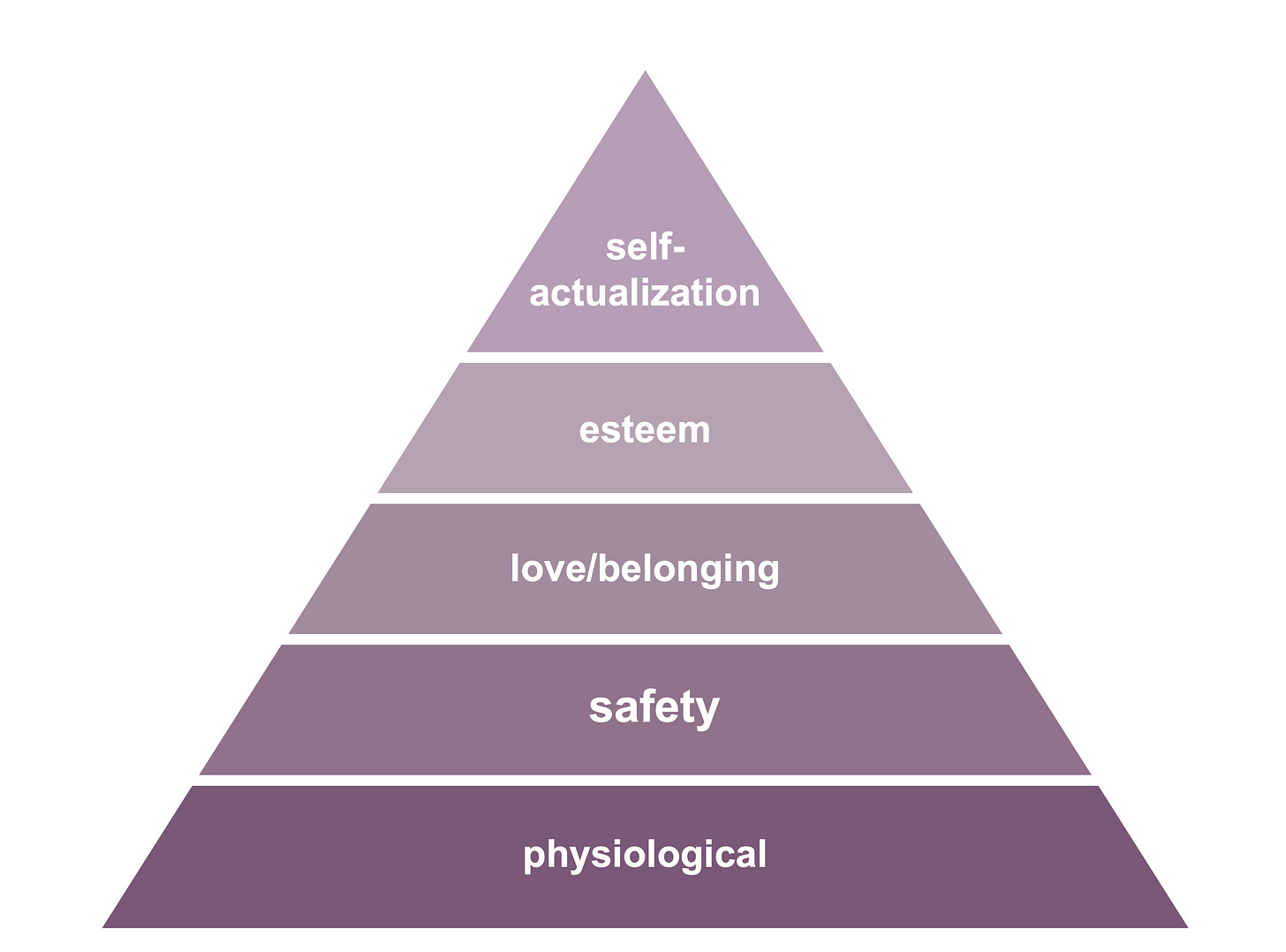

Fig 1.2. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Hello, Maslow

In the 1950s and ’60s, psychologist Abraham Maslow illustrated something we all knew implicitly: regardless of age, gender, race, or life circumstance, humans have basic needs that must be met. Maslow captured this in the Hierarchy of Needs.

Maslow stressed that physiological needs come first: breathing, eating, sleeping, and basic bodily needs. Then safety: freedom from fear, harm, or instability. Next is belonging—love, relationships, intimacy. Above that is esteem: confidence, respect, and meaning. At the top is self-actualization: creativity, morality, and fulfilling our potential.

This model can help us understand design goals. We could aim to satisfy only the bottom three layers—function, reliability, usability—but real fulfillment is found at the top: meaningful, emotionally resonant experiences.

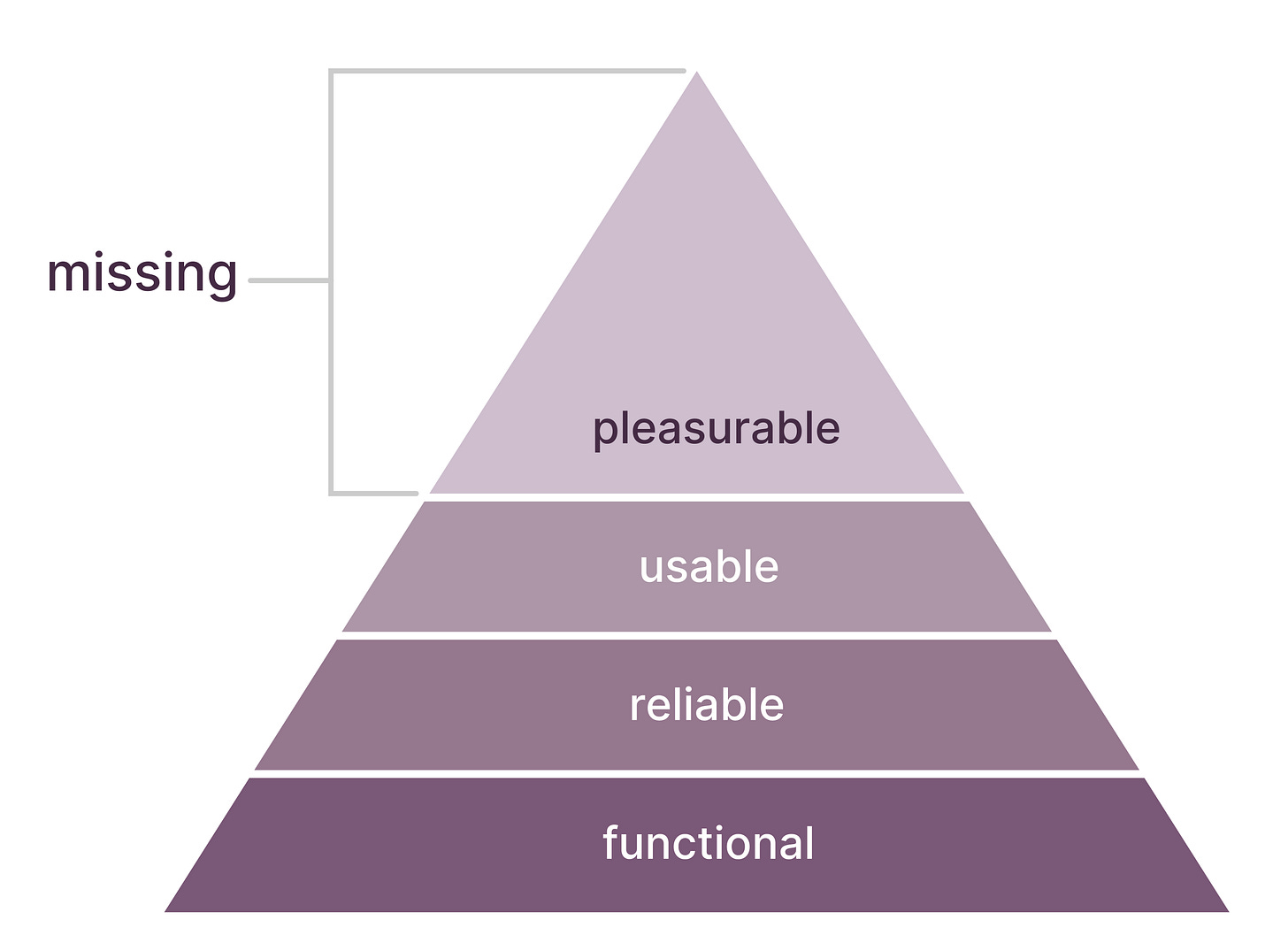

Fig 1.3. Maslow’s hierarchy remapped to user needs.

Getting the Basics Right

Here’s how the hierarchy maps to interface design:

Functional — If users can’t complete a task, they’ll leave.

Reliable — An unreliable interface quickly loses trust.

Usable — Tasks should be learnable and repeatable without frustration.

For decades, usability was seen as the pinnacle of interface design. But why stop there? We expect more from great meals, great art, and great experiences. We should expect more from digital products.

Pleasurable — A moment of delight, a gesture of clarity, or an interface that feels human elevates the entire experience.

Surpassing Expectations

Designing interfaces that are merely usable is like a chef preparing food that’s merely edible. Think back to the best meal you’ve ever had. The pleasure of the experience—not nutritional value—created the lasting memory.

Why settle for usable when we can create experiences that are usable and pleasurable?

Headspace: More Than Usable

Headspace, the meditation app, builds emotional design into every touchpoint. Meditation can feel abstract or intimidating, but Headspace disarms this through simple, warm animations and approachable metaphors.

Press “play,” and the circle containing the button gently undulates—mimicking the unpredictable drift of the mind. It’s reassuring and human.

Fig 1.4. Headspace uses endearing animation to make mindfulness accessible.

Emotion and Memory

Emotionally charged events persist longer in memory and are recalled more accurately. The amygdala releases dopamine—our brain’s “remember this” Post-It note—whenever something emotional happens.

Positive emotional stimuli in an interface can encourage repeat engagement. Headspace’s design, far from superficial, builds positive memories that reinforce the habit of meditation.

Intuit: Owning a Moment

In 1983, Intuit founder Scott Cook started a “Follow Me Home” research program, sending employees to observe customers installing the software in their homes. Although the practice evolved, the empathy it cultivated became the foundation for Intuit’s design ethos: Design for Delight.

TurboTax designers later reframed this as finding “ownable moments”—points where emotion spikes and thoughtful design can make a profound impact.

One example occurs when TurboTax asks users whether a loved one has passed away. Instead of breezing past it, the interface pauses to say:

“We’re sorry for your loss.”

This tiny moment of humanity has brought users to tears—and brought them comfort.

Fig 1.5 TurboTax acknowledges an emotional moment with empathy.

The Emotional Design Principle

People will forgive shortcomings, follow your lead, and sing your praises if you recognize and respond to their emotional state.

This is the emotional design principle.

To engage emotionally, let your brand’s personality show. Share the humanity behind your work. Emotional design turns casual users into believers. It offers a safety net when things fail. It’s not just about copy or animations—it changes how you communicate.

Misused, emotional design can backfire. If personality compromises functionality, the experience becomes frustrating. We need to understand human firmware—our shared psychology—to use emotional design responsibly.

Keep reading. Get the book!

Download Designing for Emotion and the entire Design Better library by becoming a Premium subscriber.