The Brief: Design thinking in the age of AI

In this issue of The Brief:

Design thinking in a new era

Recent job openings

Things to read, watch, and cook

Design Thinking in the Age of AI

by Eli Woolery

Editors note: We’re updating and excerpting a section of the Design Thinking Handbook, as part of this free edition of The Brief.

What does it mean to be a human-centered designer in the age of AI? This is something my colleague Bobby Hughes and I have been asking ourselves since we started running our AI+Design Thinking workshops this past Spring. In the past few months, we’ve learned a lot about how people want to apply generative AI to their design process, where they struggle, and where they’re succeeding.

As our friend and former podcast guest Kevin Bethune says, design and design thinking aren’t the same thing, but they are very connected with each other, and in this edition of The Brief we wanted to share some of the things we’ve learned about using generative AI (GenAI) in the design thinking framework, that we hope will be helpful whether you’re an individual contributor or leading a team.

In my view, design and design thinking are two different things but deeply connected.

Kevin Bethune, author of Reimagining Design

We’ve excerpted a chapter from our Design Thinking Handbook about ideation, and we’ll share some tips and learnings from our workshops as call-outs within the chapter. Broadly speaking, we see four areas areas when GenAI plays well with design thinking:

Getting started: Get to “good enough”/low-fi more quickly

Examples: Capture notes via voice and summarize, craft a screener email, suggest secondary research

Create variations of what I started

Examples: 2x2s, Brand styles

Extend my skills: Fill capability and knowledge gaps

Examples: Code a prototype, generate UX copy, create a storyboard/illustration

Push my thinking to new levels

Examples: Brainstorm more ideas, modify my approach/process, encourage new considerations like environmental/political impact

Now, on to a chapter excerpt about ideation and brainstorming…two aspects of design thinking where AI can play a big part.

Design Thinking Handbook: Ideate

The Apollo 13 Mission Control team faced a huge number of seemingly insurmountable obstacles after an oxygen tank exploded on board the 1970 mission to the moon. They needed to find a new route that would get the astronauts back to Earth quickly with a limited supply of life-supporting fuel and power.

The most pressing problem was a buildup of carbon dioxide in the ship. Without a replacement scrubber, stored out of reach in a different module in the craft, the crew would soon asphyxiate from their own exhalations.

In the 1995 movie version of this dramatic event, Apollo 13, Flight Director Gene Kranz (played by Ed Harris) assembles the top engineers and scientists in a room for a brainstorming session. He tells the group to forget the flight plan, and that they would be “improvising a new mission.” Standing in front of a chalkboard, he quickly sketches the original route of the ship. Then, when one of the engineers suggests a new route, Kranz alters the original route to show a slingshot approach that would use the moon’s gravity to whip the astronauts back toward Earth.

In a later scene, a group of engineers tasked with devising a new filtration system dumps the same items aboard Apollo 13 onto a table. They proceed to prototype a fix that the crew can build from the objects at hand, ending up with a literal “duct-tape solution.”

In each case, the route to resolving the problems seemed relatively straightforward, if fraught with urgency: get a bunch of smart people in a room, and have them collectively come up with ideas until the best solution was found. We can assume that the film was faithful to what happened in the real life control room in Houston, but what conditions created such a successful environment for brainstorming?

The term “brainstorm” was popularized by the ad agency executive Alex Osborn in his 1953 book Applied Imagination (though he had outlined his method in a 1948 book, Your Creative Power). Osborn claimed that by organizing a group to attack a creative problem “commando fashion, with each stormer attacking the same objective,” creative output could be doubled.

Osborn created 2 main rules for a successful brainstorm:

Defer judgement

Reach for quantity

Deferring judgement reduced social inhibitions in the group—no one would be stigmatized for shouting out a crazy idea. By reaching for quantity, participants would boost their overall creative output and increase the likelihood of coming up with innovative solutions.

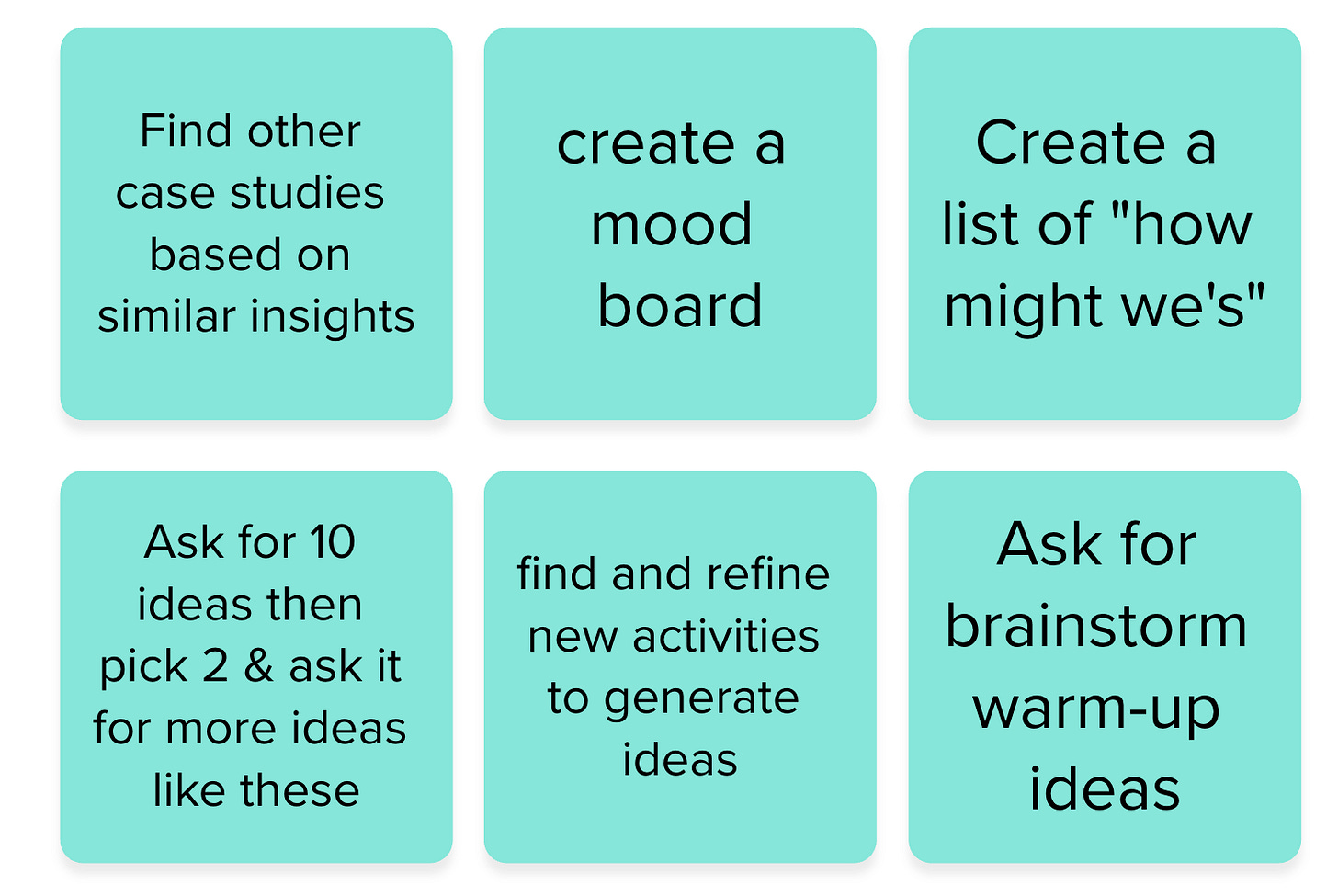

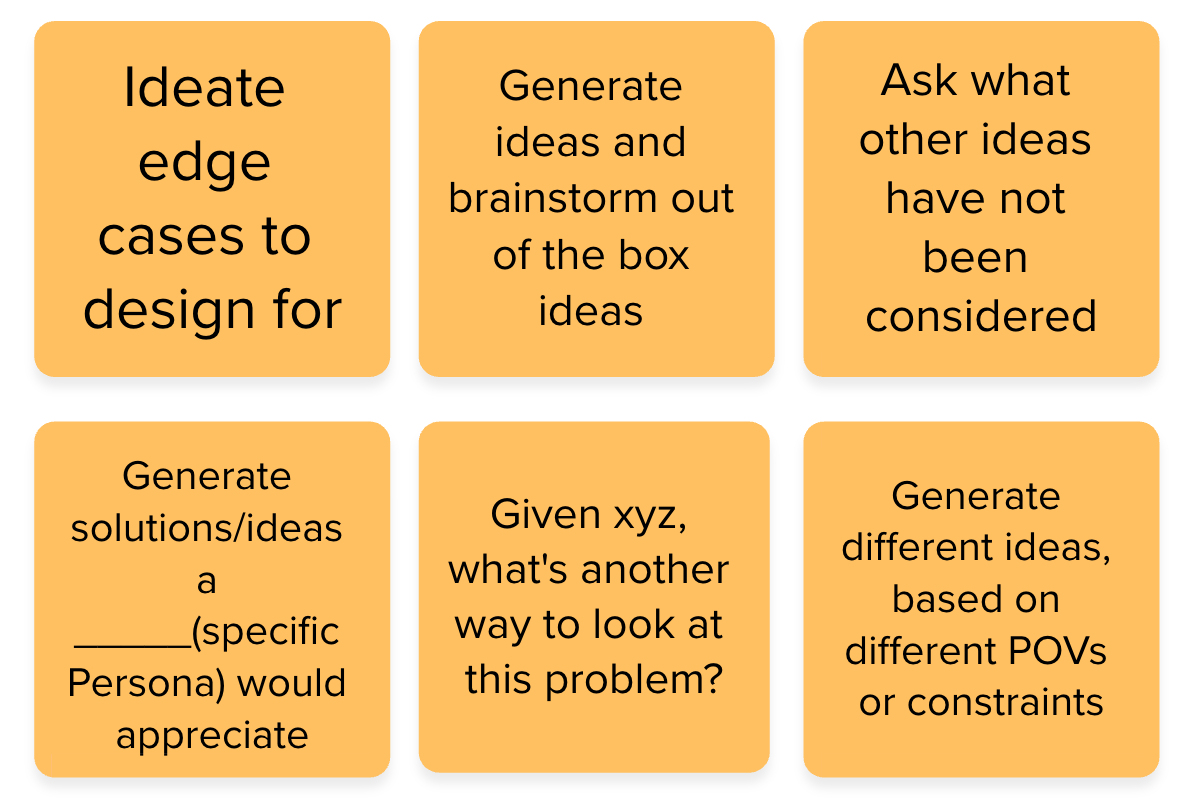

Getting started: in the category of getting inspired, and past “blank page syndrome,” here are some ideas that our workshop participants came up with for using GenAI in the ideate phase of design thinking:

Brainstorming in a group might not work as well for original ideas, as compared to individuals working independently. However, brainstorming adds value to the creative process in ways that don’t just involve coming up with ideas.

Brainstorming isn’t about new ideas, really

It turns out that the power of brainstorming doesn’t really come from spontaneously generating new ideas. Rather, the real strength in brainstorming stems from the process’s ability to:

Quickly generate lots of ideas, to help get an overview of the conceptual landscape. These are not necessarily new ideas (or good ideas). They may have been brewing for a while as individuals considered the problem beforehand. These ideas can become the seeds for solutions, to be investigated with prototypes.

Gather a team into a physical space where everyone can share perspectives on the problem and become aware of the potential solution spaces as they are surfaced. Done well, it can energize a team (and done poorly, it can deflate one).

Get clients or stakeholders to buy into the design process, and also learn what is important to these decision makers.

I don’t believe the value of brainstorming is the ideas generated; I believe it is the shared value/evaluation context created. The experience of brainstorming creates a group of people with a shared perspective, and an understanding of each other’s communication styles, who are then capable of providing a useful and powerful critique of future work on the topic.

Tim Sheiner, Cisco

Generating ideas, sharing perspectives, and gaining stakeholder buy-in are lofty goals. To achieve them via brainstorming requires careful planning. In the next few sections, we’ll cover how to properly set the stage for success.

[Brainstorms are] excellent at helping clients buy into the creative process…they get to join in on the brainstorms, they see lots of ideas, they get to vote for their favorites and a dialogue happens during the voting process that is crucial. Some kind of sorting always follows a brainstorm, and it’s during this process that one can learn from the client. What have they already done or are currently doing? What can’t they do? Won’t they do? And most importantly, what are they excited about?

Yona Belfort, VP Hardware at Minnow

Prepare for brainstorming success

Before we dive into suggestions for making your brainstorms more successful, a caveat—just like any other creative tool, there are a lot of ways to run a brainstorm, some of which might work better for certain types of problems. The only way you’ll learn which technique works best for you is to experiment with a few.

You’ll remember from our introduction that Alex Osborn sets 2 guidelines for a successful brainstorm:

Defer judgement

Reach for quantity

While these are fundamentally important, there are a few additional guidelines that will make your brainstorm more successful.

Before the brainstorm

A key part of the brainstorming process is the facilitator—someone who will lead the session, keep track of time, and set up the space for the group. This facilitator can also make sure that the group comes prepared with a mission framed by problem statements.

Set a mission

Your brainstorming session should have a clear goal. What problem(s) are you surfacing ideas for? What is the best method for coming up with this goal?

Push your thinking: workshop attendees came up with many ways to take brainstorming sessions further than the initial results

Recall that Stanford’s d.school design thinking framework (below) alternates between generative (flaring) and selective (focusing) phases. As you empathize, you gather data and stories from your users, generating insights and flaring out.

As you begin to synthesize that information and come closer to defining your point of view (POV), you become selective about the solution space you will pursue, and you focus.

In the current Ideate phase, you flare out again as you generate a multitude of ideas and select promising solutions for prototyping. Doing this helps your team step beyond obvious solutions, harness the collective creativity of the team, and discover new and unexpected areas to explore.

How do you go about generating those ideas? The POV that you generated in the Define phase is a great platform to help start the process. Using your POV problem statement, come up with “How might we … ?” topics that are subsets of the entire problem. If your POV is well constructed, these topics should fall naturally out of it.

For example, let’s go back to Doug Dietz’s POV1.

“We met scared families trying not to fall apart during the hospital visit. We were amazed to realize that they have to sedate 80% of the children between 3 and 8 years old, in order to have them be scanned. It would change the world if we could capitalize on the child’s amazing imagination to transform the radiology experience into a positive, memorable adventure.”

With that POV, you can pretty easily come up with problem statements like “How might we make the MRI scanner a more imaginative space?” or “How can we reduce anxiety before appointments by sparking children’s imaginations?” With these topics, you can then set up brainstorming sessions to surface a lot of ideas.

Set up the space

For a good brainstorm to happen, the energy in the room needs to be right. First, pick a space that has large whiteboards or room on a wall to set up poster-sized Easel Pads. The room should also be somewhat enclosed if there is a worry about bothering other teams (brainstorming can get boisterous)—but there are alternate techniques for a quiet brainstorm, which we’ll get to a little later.

Get into the right headspace

If you’re coming into a brainstorming session from individual work, it can be a little jarring to adopt a collaborative mindset—and hard to ramp up your energy level accordingly. The facilitator should spend a few minutes getting everyone acclimated. There are quick, improv-based techniques for this, like Sound Ball or Knife, Baby, and Angry Cat. You can also use the 30 Circles Exercise that we outline later in this article.

Limit the time

A brainstorm can quickly run out of steam if the facilitator doesn’t establish time limits and keep the conversation moving. Setting a time limit for each topic is a good idea (15–20 minutes works well, depending on how many topics you need to cover). You can also set a goal for the number of ideas per topic (e.g., 100 ideas in 20 minutes). Use a Time Timer so everyone has a visual indicator and benefits from adrenaline-powered sprints as the time begins to run short.

During the brainstorm

When the brainstorm kicks off, the moderator’s job is to keep the momentum going, stay on topic, and make sure all ideas are captured.

Always say yes

To keep the energy high and the ideas flowing, a good brainstorm shares a lot in common with the improv technique of “Yes, and … ” When an idea is put forth, participants should be encouraged to build on it, putting a positive spin on the contribution. Critical energy can be diverted into productive ideation in this way. For example, “Yes, I like that idea, and we could go even further by … ”

Stay on topic

In the heated environment of a brainstorm, it’s easy to get sidetracked and start diving down rabbit holes that have no relation to the problem statement at hand. It’s important for the facilitator to gently guide participants back to the current topic. Sometimes this is best done by noting adjacent topics and mentioning that the group can come back to it later or during a future session.

Be visual and headline

One way to run a brainstorm is to have the facilitator serve as scribe, logging all the ideas as they come. Another is to arm the group with sticky notes and sharpies, so that they can walk up to the board, verbally share an idea, and put a summary of the idea on the board.

Either way, it’s important to be visual. Encourage quick sketches— these will help to clarify and group ideas.

Extend your skills: Workshop attendees also came up with many ideas to use GenAI to extend your knowledge and creative capabilities during the ideate phase of design thinking

Also, ideas should be headlined as they are produced. A participant can say, “We could create a way for the user to leave feedback for us directly via a comment form,” which someone would then summarize as “Feedback comment form.”

Whatever method you choose, ideas should be shared one at a time. This allows the scribe to write them, or the participant to be heard as they post their idea to the board.

After the brainstorm

When the brainstorm is finished and there are a hundred ideas on the board, it’s easy enough to give high fives all around and walk away without really having accomplished much. Leave a little time after the brainstorm to review and capture the ideas that were shared.

Narrow down, but not too fast

If you’ve run a productive brainstorm, you’ll likely have a lot of different ideas on the board—some funny, some weird, perhaps some verging on insane. It can be tempting to cut any idea that isn’t feasible, but by doing so you may be tripping up the ideation process. Sometimes good ideas can come from a place that initially seemed silly.

Instead, give the participants a way to select ideas across multiple criteria. One way to do this is to use color-coded sticky dots or pieces of colored Post-its. Each color can signify a person’s top choices in each category, such as the lowest hanging fruit, most delightful, or the long shot.

Capture and move to prototyping

Once you’ve selected ideas in each category, carry them into prototyping, ensuring that you don’t walk away from the session with just the safest choice. Use a phone to photograph the whole board, and then extract the top ideas in a document which can be used to kick off the prototyping process (Google Docs is great for this).

Prototyping is a flaring part of the design thinking process. Even if a selected idea is so crazy it doesn’t seem worthy of a test, figure out what’s attractive in that solution, and use that to inspire a prototype. The goal is to come into the prototype phase with multiple solutions to build and then test.

Remember that brainstorming is just 1 step in the process of coming up with a solution. In all likelihood, you won’t come out of a brainstorming session armed with the exact idea that you’ll bring to your users. But you will hopefully compile an overview of the conceptual landscape, gain a shared perspective on the problem with your team, or get key stakeholders to buy into the design process. All of these things will help seed the minds of your team.

This is an excerpt from Chapter 4 of the Design Thinking Handbook. Design Better premium members get access to the book for free, as well as other titles that will be added soon, including Principles of Product Design by Aarron Walter, and Design Leadership Handbook by Aarron Walter and Eli Woolery.

The opportunities to apply GenAI to your design workflow don’t stop with ideation, of course, and we continue to learn new ways to apply it to the design process from the workshops we’ve been running. One of biggest benefits we’ve seen for our participants is giving them the time and space to play with the tools, and learn together, as Robin Staley, one of our former participants, shares here:

I had the chance to participate in the second session of the "AI+Design Thinking" workshop. Eli and Bobby did an amazing job hosting, which left a lasting impression on me. It was great to listen and engage with a diverse group of design professionals share their experiences and to undergo the complete design thinking process with the integration of various GenAI tools.

AI is here to stay and if you're looking to implement it into your workflow or just want to learn more about the subject, this workshop is a great starting point.

—Robin Staley, UX Designer II, LexisNexis

If you’d like to participate in an upcoming public AI + Design Thinking Workshop, just fill out the short form below and we’ll let you know our next availability:

We’ve also been running these workshops for Fortune 500 design teams, including tech companies developing AI tools and autonomous vehicles. If your team could benefit from a one-on-one workshop, either in-person or remote, please fill out the short form below:

Job Openings

Elliott Spelman, co-founder at Polycam, is looking for a Senior Product Designer to join the team.

Polycam is a 3D imaging and reality capture company that Elliott co-founded 3-4 years ago. It’s likely the world's most widely used 3D capture platform, and the Community Page showcases some impressive examples of what the technology can do.

A bit more about the role:

The Product Design team currently consists of 3 members, and they’re seeking someone special who has a passion for creative tools, spatial capture, 3D technology, and designing innovative experiences.

Product & Design are integrated into a single team, following a 'fullstack' PD approach where designers also take on roles as researchers, product managers, and visual designers.

Polycam's customer base is diverse and spans a wide range of industries, including physical product design and manufacturing, benefiting from the platform's capabilities.

As a product-led company, the team finds it incredibly rewarding to apply user research and need-finding skills, particularly those cultivated in the JPD.

Daniella De Sostoa, Manager of Research and Design at Ahold Delhaize USA, is hiring for a role on her team.

Ahold Delhaize USA provides services to one of the nation's largest portfolios of grocery companies and is actively seeking top talent. The team is on a mission to shape a future where human-centricity is at the core of leading local food shopping experiences. In this player-coach role, you'll work closely with your team, fostering a culture of innovation, collaboration, and enjoyment. Join this exhilarating journey to make the future of food shopping as enjoyable as it is human-centered.

For more details, view the LinkedIn post. Interested candidates can apply here.

Fun things to watch, read, and cook

Yuval Noah Harari's new book Nexus looks at how the flow of information has shaped human history.

If you’re looking for a quick primer on the history of branding, check out 10,000 years of branding explained in 6 minutes by Debbie Millman

In the US, the upcoming election is on most people’s minds, and Dana Chisnell explains why Democracy is a design problem

Radical, dude! The origin of the '80s aesthetic via Vox

Former DB guest Tony Fadell shares the first secret of great design

Dad joke of the month: Every time I get to work I hide. Because good employees are hard to find.

Finally, if you’re looking for a fun fall appetizer, try this croquettes with smoked rockfish recipe that Eli adapted from a recipe by Daniel Boulud. And for the story behind the recipe, check out his profile on The California Table:

Best ways to support our work

Gift a Premium membership, it’s just $7/mo or $72/yr

Addendum

We used NotebookLM*, a "personalized AI research assistant" from Google, to turn this issue of The Brief into a “conversation,” and also animated a clip from it.

(full “conversation” below)

Doug Dietz is an industrial designer at General Electric, who helped redesign the experience for pediatric patients that need MRI scans. You can learn his whole story in Chapter 3 of the Design Thinking Handbook.